Social Justice's Forbidden Word

"holding a grievance, or a sense of being victimized by life, while there are somewhat useful short term kind of responses, long term, they don't lead to good mental health." - Dr. Fred Luskin

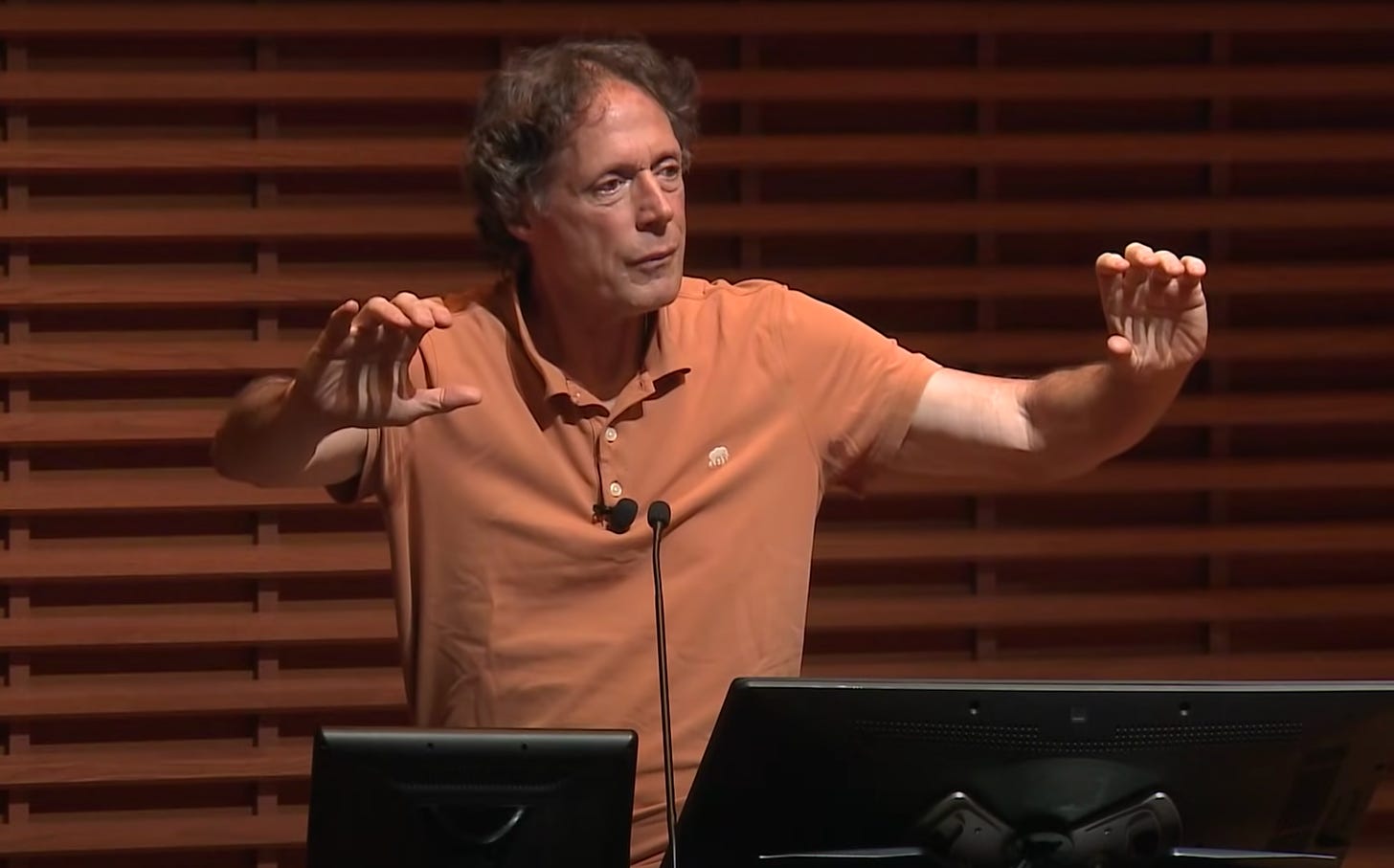

I recently had the privilege of talking to Dr. Fred Luskin, the author of Forgive for Good and one of the world's leading experts on forgiveness. He is also the director of The Stanford Forgiveness Project, and is on the Board of Advisors for the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism. Below is a transcription of our livestream conversation, and I hope you find his words of wisdom as insightful as I did.

Kimi: The first question is kind of flipping the script a little bit, because I know you talked a lot about forgiveness, but I want to start with this question. What is justice? What does justice mean to you?

Fred: What does justice mean to me?

Kimi: Yes. Whether that's day-to-day interactions—interpersonal slights that we experience?

Fred: Oh, boy—a nice, simple question! I don't know that there is a simple, easy answer to that question because I'm going to say it's a perception of some kind of either fairness, or that things turned out the way they were supposed to, or that an appropriate reaction was given to an action.

So, justice is some piece of that, but it's all perception.There is no objective fact of it. It's an experience, it's an observation. It's a processing of the individual or the group's experience around something else. It's a really tough question.

Kimi: Okay. Thank you so much for explaining that. And I understand that you are the director of The Stanford Forgiveness Project—would you mind letting people know about what that is; what research you've found through that?

Fred: I mean, The Stanford Forgiveness Project started is just a fancy name for my dissertation study. It was many years ago, and I was one of the first two or three people to do any research on forgiveness.

And so then we called it The Stanford Forgiveness Project to start looking for grants. The results of forgiveness research are that for the individual, it reduces stress when you become more forgiving. It has some salutary impact on physical experiences, and it is a healing quality generally in relationship. Probably the most striking is what it does for one's mental health and for one's sense of efficacy in the world because unforgiveness, or holding a grievance, or a sense of being victimized by life, while there are somewhat useful short term kind of responses, long term, they don't lead to good mental health. They lead to a kind of helplessness, often a sense of anger and even responding to what you assume for some sense that justice was not served.

Kimi: I'm curious, have you been paying attention to social justice movements of the last decade, especially when it comes to racism or injustice due to differences in identity?

What are your observations on modern social justice, and do you think it is lacking a balanced, healthy injection of forgiveness?

Fred: I think one of the human flaws is to take our current experience or the world's current experience and make-believe it's new. Human beings have struggled, since they've been human beings, to balance the personal and the more global impersonal.

So I have certain identity qualities, and I'm also just another human being passing through here. You have certain identity qualities, and you're just a human being passing through—and it's really hard to keep those in perspective.

The social justice stuff: I think most people want social justice, they just define it differently. And so it relates again to that idea of justice as a perception. I'll give you an example of what I would consider an abstract, but a tangible example from right now. I know there's discussion on reparations for slavery, right?

Kimi: Yes.

Fred: So you could have some people who could make a legitimate argument that black people were harmed by being slaves and then that harm has continued on until the current day because of the mistreatment.

You could make that argument and then it would have merit. And yet you could also make an alternative argument that what happened X number of years ago for me now, I had nothing to do with that. And so you would end up with two very different perceptions of what justice is. But both sides would be thinking “we're going for justice.”

And so that's what's so hard about so many issues. The forgiveness piece says, at some level, I can forgive people who I don't agree with. I can forgive past actions that were hurtful so that now I may be more centered and less filled with grievance so that our accommodation, or how we work things, out may be more successful.

It doesn't mean that people get a pass. I've dealt with people who have had family members murdered in political violence and it's not like, "hey, it's okay that you killed my kid"—I mean, that's horrifying! But if I'm too caught up in just my identity as someone who had a murdered child, then I sometimes run the risk of not seeing things clearly because I'm over-identified with that part of myself.

So I hope you are grasping some of the subtlety I'm trying to bring into the conversation.

Kimi: Yeah! My experience with forgiveness has been that I was perceiving a lot of injustice in day-to-day life. And based on my identity as a black woman (I'm originally from Uganda and I moved to the States ten years ago) I learned, in college, that there is much more racism against me than I'm aware of.

I was taught that I needed to become more aware of these acts of racism in order to rectify the racism in day-to-day life. However, that caused me to become more cynical, caused me to become more negative and led to depression and anxiety in my day-to-day life, which led me to perform less than my peers who weren't using that lens—who weren't seeing day-to-day interactions as terribly as I was. It wasn't until I had a light bulb moment where I realized, you know what, most of this is just me taking offense at will.

Even without knowing someone's motive by just saying, you know what? I think this is racism and not talking to them, I'm not going to figure it out. I was just keeping myself weighed down with hundreds of grievances a day and couldn't get out of bed, had periods where I couldn't work, couldn't hand in assignments until I started to forgive and just say, "you know what? I release this. I bless them. I let it go." That's when things started changing.

It became such that I wasn't only forgiving past incidents, but I could no longer see future or just, you know, day-to-day interactions as racist to the degree that I used to. It changed not only the past for me, but it also changed the way I perceive day-to-day interactions and it infused grace.

So I have seen the benefits of that forgiveness, but it has taken a lot. It's been hard to describe to people. Whenever I tell people about my experience with racism, microaggressions and forgiveness, they think I'm being insensitive to their struggles. And so I wonder for you—for anyone who was in my previous position—what would you recommend as steps to testing out forgiveness?

Say, if someone's like, "this sounds like you're demeaning my experience", how would you convince them of the need for forgiveness in their personal life and what should they do? How do we forgive?

Fred: I'm going to give you two responses before I get to that question. One is, there is no simple external world that you live in. There's a relationship between what happens and if you say you identified yourself as a black woman, then there is racism.

I mean, that's an absolute, indisputable fact. And there's also your inner processing of that, and together that forms your reality. It's not just the racism, it's your inner processing and what else you're processing. So you can say that, yes, there is racism—I mean, it would be like saying there's air. But you can also say that that's all there is, and then you get very unhappy and very physically challenged.

Or you can say there's racism, and there's incredible human goodness and beauty. And then it holds it differently. But it's not an argument with "is there racism or not?"

It's how am I reacting to and dealing with the racism and what kind of person do I want to be to best work with that racism? That's taking more responsibility inside of yourself.

Second, there's a lot of experimental data that shows that saying 'racism' (or saying anything) is not really meaningful unless you include your definition of 'racist'. So you can have people who completely disagree as to what racism is, it doesn't make them right or wrong.

You could say it's an overt act of hurtfulness or discrimination, while somebody else could say it's a look or it's something that happened a hundred years ago. So the problem is—as you discovered—once we train our minds to find something, we expand our definition and categories. And there is experimental research that asks people to find things. One of the great experiments is to find the color red.

In this experiment they put a lot of colors and told people to find the red, and then they found the red. But now they get rid of most of the red, but they have shades of things and they have more blues. But as long as the people's instruction is finding the red, they keep on finding red. That's less red than it used to be.

And so the mind also follows the direction of its intention. Once you made an intention to find racism, there's a huge amount to find it, but the definitions have probably grown dramatically. So without some agreed upon starting point of finding, it becomes meaningless.

Kimi: Right. Wow.

Fred: I'm just telling you, what you said is a very strong example of the problem with harsh opinions—global labeling of things. Because once you decide what they are, and you no longer specify exactly what we're looking for, then you just keep on finding more of it because of what your mind does.

The most important antidote to that is twofold. One, some training of the mind also to find beauty and goodness in this world. If you don't do that, the negativity bias of our minds, which is omnipresent, will expand and find what it is we want. When you say let me find racism, you can also—if you really wanted to find racism—you could also change your mind to find people who have overcome racism, or who have limited racism, or have an incredible tolerance of diversity.

Racism is not just a one-sided negative experience that is stuck in time. It's a broad relationship of human beings—relationships to people who are different than they are. So with any thing, you have to actually teach yourself to find the good around it and the beauty, and people who aren't, so that your view of the world becomes a deeper, truer view.

The second piece is you have to calm down. So you can say "here's racism", but if you release adrenaline every time you find racism, then you've altered your mind and body to be on the edge all the time and your thinking becomes distorted.

So this 'calming down' involves meditating for a moment, counting your breaths, looking out the window for something beautiful, remembering that you're loved. Turning away from the stimulus. Those will quiet your adrenalized response and you will be able to go, "Oh, here's an instance of racism. So what?"

Or it's just one that exists, or I don't have to react to them all. Or, people are allowed to be imperfect. So you can see it, but not react in a way that gives you a deeper, worse view of people in reality. And then you can be open to making very different decisions about it.

Kimi: Wow. That was very helpful. Do you think with our modern addiction to notifications and our phones and learning the latest news headlines—do you think this is impeding our ability to calm down and therefore being able to forgive and look for the good?

Fred: Absolutely. Both. The media's enticement to get an audience is certainly impacting on nervous systems. Social media is hijacking our nervous systems, but then our tribalism is also impacting that, because then all our reactions are kind of joined with who we align with and who we don't align with, and then it becomes dangerous. So let me just give you an example.

Like you said, you became somebody who found racism everywhere. That, in and of itself, is not a terrible thing if you're calm enough, and your story is enough of heart that you can say, "Wow, there's racism in a lot of places." Now, what would really be valuable to that? Well, one might be that "I get rid of whatever racism is in me so that I don't contribute."

That would be a really useful thing for this world when you encounter racism. How do I learn to talk about it so that I don't see people who I think are racist as my enemies, but as shared people on the planet with whom we can have a reasonable discussion around this? Then you wouldn't have been so burdened by what you saw.

But you had become tribalized, which is "racists are bad. We have to stamp them out. They're not me. They're the other." That is a terrible influence, and that is what exhausted you.

Kimi: That is crazy. It's such a revelation to realize that there is a very key element of saying I also harbor that same imperfection—I am not perfect.

I think that's what drives that sense of "everyone is committing a trespass against me because I'm perfect, I'm innocent." And that's what drives that anger and that grievance.

On another note, I'm curious about the more serious cases that you have looked at. Say, cases where people have dealt with murder. How does the victim of such atrocities get justice but also grant forgiveness?

I know a lot of people confuse forgiveness for saying I'm letting the criminal off the hook. But in your research, what would you recommend for those who have suffered serious harm, who need a sense of justice, but also who need to forgive but have trouble differentiating between the two?

Fred: I mean, in this imperfect world, there isn't always perfect justice and secondly, there are implications of individuals thinking that they know what justice is.

My guess is that when you were at your most heightened state of finding racism everywhere, you had a very different understanding of justice than you do now, because you probably wanted to punish everybody, and you probably wanted to stamp them out because what they were doing was so terrible. But now that you're not as infected by that kind of virus, you can:

a.) Have more compassion for them;

b.) See that justice is a very tough situation because everybody's in a different place.

And somebody may say "they're just words, get over it" even though they don't behave in any way that mistreats people. But in the comfort of my home, I can say whatever the heck I want, and what you might perceive as justice, they might perceive as "get your nose out of my business!"

And so that's the undercurrent of a kind of forgiveness that says if I look inside myself, I see how much I need to be forgiven for, therefore, I'm going to assume that most people are at least as wacky as I am. They're gonna need a good deal of forgiveness too! But me personally, if whatever I'm threatened by, or affected by—if there's a more benign explanation, let me try that one first so that I preserve my mental health and my kindness.

Let me try that first. And if that doesn't work, maybe then I go to more harshness. So, the justice from the beginning is, well, let me not try to escalate this. Let me try to make peace. Let me try to, at least in my own heart, have a little compassion for people who may be stuck in ways of being that I don't want them to be stuck in. But they don't all have to become my enemy.

And then the victim piece is like when you were hypersensitive, you were much more of a victim than you are now. And so people don't recognize that to some degree, they have some control over even their victim status, that you're not a victim just because other people do things that you don't want them to do.

Kimi: Yeah, wow. That is so, so good.

Fred: You have some agency in this. You have some responsibility to take care of yourself. Now, that doesn't mean that you can't identify things wrong in this world and make a concerted, positive effort to make them better. That would be my better definition of social justice: find something in the world that you think is wrong and use your intelligence, not just your hostility and your resentment.

Use your intelligence and your desire to help heal this world and participate in that in a healthy way so that you have long term sustainability and try to make the world better. That's a responsibility we all share.

Kimi: I really appreciate your insight so far. I just want to leave us with one more question—what are your key steps towards forgiveness?

Fred: My most important story around forgiveness?

Kimi: Yeah, what would you recommend to someone who is struggling with the concept but is ready to try and forgive but perhaps doesn't know how to go about it? How would you lay out that process?

Fred: Let me answer my question first, and then I'll answer your question.

One time I was teaching class and at the end of a class series, a woman came up to me and said, "thank you" and I had no idea what she was thanking me for. She said "I took your class because I hated my ex-husband.

"We were fighting all the time, and we were arguing once on a motorcycle, driving up through the hills above Stanford. And he turned around to yell at me, lost control of the motorcycle, and crashed it into a tree. But we were arguing, and I ended up in the hospital with chronic pain in my pelvis, and he ended up with brain damage from this. And I hated him. I hated him.

"But as time went by, and I started to relax a little and I took your class, I realized, first of all, that I had more responsibility for it than I had taken credit for, because we were fighting. It wasn't just him, you know? Even though he did a bad thing, it was us. And two, why would I want him to suffer?" So she told me at the end of the class that she had started visiting her husband.

They ended up getting divorced, but she helped take care of him because she had forgiven him and the forgiveness, she said, dramatically reduced her pain.

Kimi: What!?

Fred: Yeah, because she was angry all the time.

And you can apply that to anything. That is what the essence of forgiveness is. You stop blaming something outside of yourself for ruining your day.

And this doesn't mean that these things are not bad, but you don't spend your day blaming them for ruining your day. You go out and do something positive about it—that's the shift of forgiveness.

It's like Desmond Tutu says, without forgiveness, there is no future. What that means is if you're just seeing racism, you're not seeing hope and you're only seeing the past evil. Then you keep on bringing that into the present. What Desmond Tutu said is that when you let go of the blame and the constant agitation about it, then you have a chance to look back at the past and make something better for your present and future. And that's the essence of forgiveness.

So you start by taking responsibility for what's going on between your ears, and you recognize what you're doing right now to give yourself an unhappy present.

And so you slowly disentangle yourself from whatever you thought was causing this unhappy presence. You can say to yourself, I don't have to be angry at this 8 hours a day. And that's improving your mental health. These are all basic mental health principles. If you want to get through this difficult life without being miserable, these are the kind of things people have found to do that reduce your misery.

Then you can go at whatever it is you wanted to go at from a kinder, more open hearted, more hopeful perspective. And that will help you do so over the long term. You won't burn out as much if you're not pissed and you won't antagonize people all over the place, so they are not pissed either. And so you become more effective.

Kimi: Wonderful. Thank you so much for everything you've shared today—This was golden!

No mention of technology or economics.

I used to work for IBM. I fixed computers. I did not give a damn about racism at all as long as it did not get physical. One of my White field managers admitted that I was doing a better job of servicing computers than he had. But how much of a problem is it that Black Americans do not place enough emphasis of understanding science and technology.

It is technology that made it possible for Europeans to go around the world stealing land and resources not Racism. Getting emotional about the wrong thing is silly.

Black Man's Burden by Mack Reynolds

In Project Gutenberg